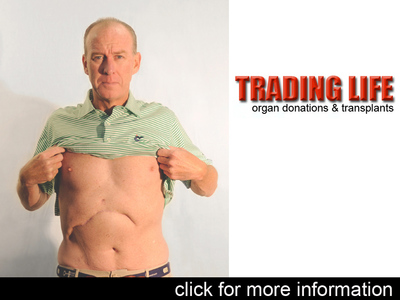

John Wilhide's life moved from the fast lane to slow lane, as he describes it, since his life-saving liver transplant.

On June 8, 2013, the 50-year-old Baltimore man celebrated his 50th birthday. His family took off for a month-long vacation. He was going to meet them in week. But he never made it.

He was playing golf at the Burning Tree Club in Washington D.C. in late June when he started having symptoms of jaundice, a yellowing of the skin and eyes. He said he was experiencing persistent itching and continued yellowing.

Doctors thought it was acute Hepatitis.

They were wrong.

His wife headed home to Baltimore where Wilhide was checked into Mercy Medical Center. Doctors concluded that Wilhide had an extremely rare cancer of the bile ducts. It's called cholangiocarcinoma, a disease less than 1 percent of the population is diagnosed with annually.

It was then that Wilhide began to think he was not going to make it to 51.

"When I was diagnosed, at first I was very scared," he said. "When I received the news, all I could think was I really had no chance of survival," Wilhide said.

The cancer was caught in the early stages, which qualified Wilhide for -- at the time -- a new Mayo Clinic protocol of removing the cancer with a liver transplant. The cancer was otherwise inoperable.

"When you go through radiation and chemotherapy, you have bad days," Wilhide said.

Teams of doctors guided Wilhide and his wife through the process. His confidence grew. But the last 10 days before Wilhide's procedure brought him to the brink of giving up.

In late January, his system began to fail. It was 3 a.m. on Feb. 10 when the call came in. Wilhide's wife answered. On the other line was a transplant team from the University of Maryland Medical Center.

"We have a liver for your husband," Wilhide said reenacting the call.

- READ | The Boswells: Daughter's death saved three lives through organ donation

- READ | Amy Sherald: 'I learned to fall in love with the idea of death'

Wilhide had been in a toxic state for 10 days up until that point.

"The poison was getting through my blood stream," he said.

The "poison" was seeping from an abscess from his liver.

"I was hallucinating," Wilhide said. "When I thought I was communicating with people I wasn't getting feedback. … I said some things that were inappropriate and some things that were funny. At the time I didn't really know if I was alive or not. It was almost like an intermediate state."

When his wife arrived at the hospital, Wilhide had all but given up.

"I told her, I just want to get out of here," he said. "She said, 'you're not going anywhere but the operating room.' I immediately broke down. It was my first cognitive moment in 10 days."

He was out of surgery and in recovery by 3 p.m.

"You go through every emotion you can possibly think of: happiness, crying for happiness, crying because your scared," Wilhide said. "My wife … she was a rock. My doctors were always positive."

Wilhide used to describe his life as a 120 m.p.h. run down the Autobahn. He has since taken a step back from his high pressure life in commercial real estate.

"Things that are so important to me now, I did not see," Wilhide said. "Every minute I can spend with the family I treasure. My boys are 8 and 3 and having the ability to spend more time with them has been the silver lining to all of this."

He's also more cautious about his health now, a change in his life that he made not only for himself, or his family, but for the man who died to give him a second chance.

"We pray for our donor family every day because when you really think about how somebody can actually think about somebody else in a time of sorrow is amazing, amazing to me," Wilhide said. "It's a complete 180 for me -- where I spend my time and focus."

Wilhide said he was struck by the similarities he had with his donor. They both attended then-Loyola College. They shared friends. They both had big, supportive families. And they were both big Ravens fans.

RELATED:Organ recipients share connection with donors

"We've come to find out that there were so many links of commonality once we met the family," Wilhide said. "The more I hear about him and the more I, … we lost a very, very, very good man.

"I'm truly blessed to be the recipient of his organ," Wilhide continued. "We have had dialogue with his wife and son and best friend. … I see that relationship continuing. It's very hard for me when somebody lost their life to save mine. You live on and treat yourself and his organ with tender care, much more than, I guess, the respect I had for myself. The more I hear about him, the more I truly feel blessed."

On Aug. 24, Wilhide will reunite with the transplant teams and the specialists who saved his life.

"You're with them for such an extended period of time they become an extended family," he said.

Take action against kidney disease with UMMC. CLICK HERE